- Home

- Auclair, Philippe

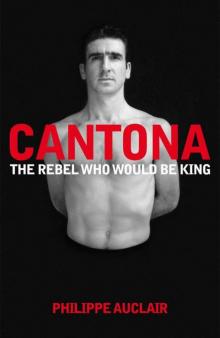

Cantona Page 11

Cantona Read online

Page 11

Desperado?

I think that’s . . . quite apt.

Provocateur?

Provocateur? . . . yes, yes.

Insolent?

No.

Haughty?

Who said that?

No one in particular. It’s a label.

Never heard it. Haughty, haughty . . . yes, that’s a word that suits me fine.

In the end, all of this makes you a media animal?

Probably. But I’m not trying to be one.

. . . and an icon for the young?

If I have a piece of advice to give to the young – as I am haughty! – it is to count on nobody but themselves to succeed. It gives me pleasure that ten-year-olds have my poster on their bedroom wall. But I ask those who, one day, will be contacted by professional clubs, to tear that poster up.

5

THE VAGABOND 1:

MARSEILLES AND BORDEAUX

‘When I was a little boy, what made me dream was the Stade-Vélodrome. And this love will never leave me. In Marseilles, I was happier than anyone else could have been in the whole wide world. My most beautiful memories are . . . my youth.’

Éric speaking to L’Équipe Magazine, April 1994

‘Unfortunately, in Marseilles, there is a culture that glorifies cheats when they win. [ . . .] The Marseillais is sometimes only proud of himself when he’s managed to get something by cheating. Because it harks back to the image of the old Marseilles, of the Marseillais voyou [lout]. Fake wide boys who think they’re mafiosi. That’s Marseilles. The cult of the mafia. The guy who steals a kilo of clementines, there he goes, he’s a mafioso.’

Éric speaking to L’Équipe Magazine, April 2007

Éric was not the only little boy who dreamt of the Stade-Vélodrome in the early seventies. The brittleness of the French national team exasperated its supporters. It suffered from staggering physical deficiencies, which nullified the technical excellence of what was otherwise a fine generation of players. Les Bleus, who did not figure in any major competition between the World Cups of 1966 and 1978, earned the dubious nickname of ‘the world champions of friendlies’, performing decently when the pressure was off, capitulating as soon as qualification for a tournament was in sight. Two clubs took it on themselves to produce football that didn’t suffer from comparison with what could be seen on the English, Scottish, Dutch, Italian and German pitches of the time. These exponents of ‘le football total’ were St Étienne, winner of seven league titles between 1967 and 1976 (as well as three Coupes de France), and Olympique de Marseille, the aesthetes’ choice, who won the double in 1971–72, and were the only rivals of the Stéphanois in the nation’s hearts. Fickle hearts they were, as they were bound to be in a country where club culture is yet to take root in 2009, thirty-three years after the Bayern Munich of Franz Beckenbauer pinched what would have been France’s first European Cup from under the nose of St Étienne, on a still-lamented night in Glasgow. It’s a story which is as deeply ingrained in the psyche of the French as England’s disputed third goal in the 1966 World Cup final is in that of the Germans. If the goalposts hadn’t been square, at least one of the two shots which rebounded on Sepp Maier’s woodwork would have gone in, and the adventurousness of St Étienne would have been rewarded with a European title in May 1976. Or so it is believed to this day.

As a native of Marseilles, one of a handful of French cities where football is more than a stick-on patch in the fabric of daily life, Éric was bound to develop a powerful attachment to the white and sky-blue of OM rather than the green of St Étienne. St Étienne was a powerful, dynamic, efficient unit, not unlike the Liverpool team of the day. OM appealed to romantics much in the same way that Danny Blanchflower’s Spurs had years before in England. In the Yugoslavian ‘goal machine’ Josip Skoblar, who scored an astonishing 138 goals in 169 games for the Marseillais between 1969 and 1975, and winger Roger Magnusson, ‘the Swedish Garrincha’, who cast his spell over the Vélodrome from 1968 till 1974, they possessed two of the most exciting players of that era. Their posters hung in Cantona’s childhood bedroom, next to photographs of Ajax’s gods, whom Éric had seen in the flesh on 20 October 1972, when they beat Marseille 2–1 in the European Cup.

Cantona, the matador, must have hoped that the shirt worn by Skoblar and Magnusson before him would be his mantle of light. But it turned out to be his tunic of Nessus. It consumed him, causing pain that the passing of years has done little to relieve. Marseille wounded the child in him, perhaps mortally, and it could be argued that his later career was an attempt to conjure back to life the youth he was stripped of by his home-town club. At Auxerre, he had rarely missed an opportunity to tell the world what he thought of the game’s milieu (not much). But one could sense teenage bravado in his expressions of dismay at what surrounded him, and that a part of him wished his instinct to be wrong. Those who doubt it should cast their minds back to what he achieved for Roux and Bourrier: footballers never lie on the field of play. But Marseille was different. The fantasies he had entertained were cruelly shown to be mere daydreams. He craved innocence, light, splendour. What he got was betrayal, pettiness and what he called a culture of cheating, a perception that would be substantiated in 1993 two years after he had left the club, when OM was found to have suborned their way to success. In the summer of 1988, though, the talk on the Vieux-Port was of the rebirth of the Phocéens.

After a decade-and-a-half of turmoil, which had seen charismatic chairman Marcel Leclerc ousted by a boardroom coup in 1972, and OM being relegated to the second tier of the league four years later, the club had enjoyed a suitably chaotic renaissance. A team largely composed of minots (local boys) had earned promotion to the top flight in 1984, and the club had been further invigorated by the arrival of Bernard Tapie at its helm in April 1986, after some forceful manoeuvring by the city’s elected monarch, Socialist mayor Gaston Deferre.

The Parisian businessman had grandiose plans for his club, which had finished the 1987–88 season with a sixth place in the league and a spot in the semi-finals of the European Cup Winners’ Cup. Money was no obstacle for the boss of Adidas, as he proved by attracting Karlheinz Förster and Alain Giresse to the Vélodrome in the wake of the 1986 World Cup. Bringing back the prodigy of Les Caillols to his home town was, at first, a popular move. It satisfied the Marseillais’ odd kind of clannish and unforgiving sentimentality, and made perfect sense as far as the team’s progression was concerned, especially after the departure of playmaker Bernard Genghini. What is astonishing is the speed at which the crowd of the Vélodrome turned against their own. When I asked Célestin Oliver why Cantona had to suffer so much abuse so early on in his Marseille career, he replied: ‘Il bouffonnait.’

He ‘played the buffoon’? Not quite. The habitués of OM perceived Éric’s haughty demeanour on the pitch as a mark of disdain, of which they were the target. In contrast, they embraced the humble but demonstrative Jean-Pierre Papin, the Golden Boot of the previous campaign, with whom Cantona was to form a lethal partnership for the French national side, if not for Marseille. JPP made no claims to be an intellectual vagabond, and was mocked mercilessly in the French media for what could be euphemistically dubbed his rusticity. Papin and Cantona formed an odd couple: chalk and cheese off the pitch, they complemented each other beautifully on it, not in the way a Zidane and a Djorkaeff combined, as if they were the two hemispheres of the same brain, but by doing their utmost to dovetail each other’s game. When Jean-Pierre’s form was indifferent, Éric would raise his, and vice versa.10 They functioned as a sort of two-man relay team, not unlike the famed duo that won the Ashes for England in 1956: ‘If Laker doesn’t get you out, Lock will.’ But the Marseillais failed to see what was blindingly obvious for neutral observers. They closed ranks around the future Ballon d’Or, because he remained true to himself, while Éric was castigated – for exactly the same reason.

It is true that there have been more auspicious starts to a club career than Cantona’s at OM. On 20 Au

gust 1988, on the day he had scored his second goal for the club in a 3–2 victory at Strasbourg, Éric’s fuse blew in spectacular fashion in front of TV cameras. He had just learnt that the French manager Henri Michel hadn’t picked him for a forthcoming friendly against Czechoslovakia. Cantona, a lynchpin of the national side since his debut a year earlier, had had no intimation that he would be rested for this largely inconsequential fixture. Michel had told his assistant Henri Émile that he ‘wanted to try out a few things and let [Cantona] have a breather’, and that he would call the player presently to inform him of this decision. But the call was never made. ‘If Michel had picked up the phone, there would have been no incident,’ sighs Émile. Instead of which an incensed Cantona earned himself a ten-month ban from Les Bleus with a tirade that demands to be included in its entirety, for the splendid robustness of its language as well as for the frequency with which it’s been misquoted over the years, particularly in England.

‘I will not play in the French team as long as Henri Michel is the manager,’ he said. ‘One day, I’ll be so strong that people will have to choose between him and me. I hope that people will realize quickly that he [Michel] is one of the most incompetent national team managers in world football.’ Then, infamously, ‘I’ve just read what Mickey Rourke said about the Oscars: “The person who’s in charge of them is a bag of shit.” I’m not far from thinking that Henri Michel is one too . . . What will people think, whoever they are? I don’t care at all.’ You will note that Cantona stopped short of calling Michel a ‘bag of shit’ sui generis, preferring to invoke the authority of a Hollywood actor who shared his passion for boxing and motorbikes, and for whom he had developed an obsession at the time – but would later identify as a professional rebel who had exploited his image to earn fame and fortune.

In the furore that followed, hardly anybody noticed that, twenty-four hours after shocking the nation, a contrite Cantona had said: ‘When I saw myself on television, I scared myself, and I was ashamed [ . . .]. This rude, uncouth person wasn’t me. Sometimes, when I have something to say, I express myself badly, very badly. I belittle people, I trample on them. It happens to me even within the family. [Michel’s] announcement of the squad cut me to the quick. I panicked. I was afraid. I think it’ll sort itself out – it is in everyone’s interest. I need them and they need me.’ His sincerity wasn’t feigned, but the apology was by and large ignored, feeding Éric’s feeling of injustice. Yes, he had made a mistake. But so had Michel. What was the use of wounding one’s pride so publicly, when it was obvious to him that ‘people’ were out to crucify a maverick called Éric Cantona, regardless of the circumstances? ‘People’ wouldn’t hear many other expressions of remorse in the years to come.

His ban – which had catastrophic consequences for France’s chances of qualifying for the 1990 Mondiale – didn’t extend to OM, for whom he played all but two of the first twenty-four games of the season, with greater success than local fans would have you believe today. But it prevented him from sharing in the Espoirs’ conquest of the European title, in which he had hitherto played such a pivotal part. The first game of the two-legged final between France and Greece, held on 24 May in Athens, finished in a 0–0 draw, with Éric assuming his normal position in the side. The return match, held on 12 October, saw Bourrier’s players run away with a 3–0 victory in their talismanic stadium of Besançon. This time, Éric, banned from the French national team until 1 July 1989, could only watch from afar. His six goals made him the competition’s top marksman, and no one had done more to give France its first success in this tournament. But at the age of 22, he had come as close to international consecration as he would in his entire career.

Despite what the press suggested, Éric enjoyed a decent – if distant – relationship with his moustachioed manager Gérard Gili, another Marseillais who had been OM’s second ’keeper in the early seventies, came back to the club in the eighties, and later showed his value as a manager by taking the Ivory Coast to the 2006 World Cup finals and the 2008 Olympics. Gili kept the Auxerre defector in the starting eleven despite a pronounced dip in his goalscoring statistics. Never the quickest of starters, Cantona had to wait until his sixth game, a 2–0 victory over Matra Racing on 17 August, to open his account. The brief flurry of goals which followed (three in three), perhaps fuelled by a desire to show Michel what he had been missing, suggested that Éric had found his feet at the Vélodrome, but he couldn’t sustain this rhythm. Unsettled by the growing hostility of his home crowd, he would score only once more in the thirteen matches to come. In January 1989, the month in which Stéphane Paille had been voted French player of the year, way ahead of his friend and Espoirs teammate (something that would have been unthinkable six months previously), Gili admitted: ‘Éric has a huge challenge to confront. He’s a man of character, and I hope he can.’ He meant it, but not everyone believed him.

Did Marseilles, the town, ever want Éric to succeed? Marseille, the club, has forgotten Éric Cantona. When I visited their museum, located under one of the stands of the Vélodrome, I searched in vain for a trace, any trace, of his stay there. None was to be found. It should be stressed, however, that the results of Éric’s team didn’t suffer much from his supposedly patchy form: OM only conceded three defeats in the twenty-two games he played before his dramatic departure for Bordeaux. One of these was a 1–0 reverse on Cantona’s old ground at Auxerre, in November 1988, where he deserved to be named man of the match. By the time Éric’s fuse-box short-circuited again, on 30 January 1989, exactly a month after Isabelle had given birth to their first child Raphaël, Marseille, chasing an effusive Paris Saint-Germain, had already built a platform from which they could spring to their first league title in sixteen years. But his indiscipline denied him a further part in OM’s appropriation of le championnat, just as it had denied him a chance to partake in the under-21s’ European triumph.

On the morning of 7 December 1988, the Armenian city of Spitak was reduced to ruins by an appalling earthquake which claimed over 25,000 lives. Hardly anyone in the vicinity of the tremor’s epicentre survived. The French and Armenian peoples have long held a deep affection for each other; Marseilles, in particular, had been a refuge for the victims of Russian, Ottoman and Soviet persecution for over a century. Charles Aznavour, the most celebrated son of the Armenian diaspora, wrote a song on that tragic occasion, ‘Pour toi, Arménie’, which sold over a million copies in France alone. Tapie, who was also a warm-hearted man capable of genuine acts of generosity, proposed that OM play a charity match against a top side from the ailing USSR. The long French winter break allowed for such a fixture to be organized without detriment to Marseilles, who could field all their stars when they lined up to face – in front of national television cameras – Torpedo Moscow on a chilly night in Sedan, on 30 January.

The choice of Sedan was, to say the least, rather eccentric. The capital city of the Ardennes region is well known for two things: its place in French history books as the scene for one of the country’s worst-ever military defeats, against Bismarck’s Prussians in 1871, and its harsh Continental climate. In the month of January, Sedan usually froze, and in 1989 it did just that. Had the match been a league fixture, it would have been abandoned without a second thought. As Henri Émile recalled – Émile, the man who was seemingly fated to be present whenever Éric lost control of himself – the pitch was frozen, so dangerous that most of the players first refused to warm up on it. The organizers insisted; so did the networks, and both clubs’ officials. Cantona ‘missed two or three balls which looked within his reach, because they skidded on the ice’, as Émile recalls it. Of course, Éric should have ignored the freakish bounces, pottered about, and waited for the warmth of the dressing-room. It was a charity game, for goodness sake. But no.

At one point, a ball hit the advertising boards and came back to him. Disgusted, he hoofed it into the stands. The referee, Monsieur Delmer, who had cautioned him when Auxerre played Marseille nine weeks previously, im

mediately came up to remonstrate with the player. Cantona replied: ‘All right, don’t fret, I know,’ adding, with what the official felt was some menace, ‘I don’t need this.’

A worried M. Delmer walked up to the OM bench to have a quick chat with Gérard Gili. Émile, who was sitting alongside Michel Hidalgo just above the dugout, could hear everything. Gili thought Cantona was ‘about to blow it’, and decided to substitute him. As others did after him, the Marseille manager found out that it was not the wisest decision to take Éric off the pitch before a game was over, whether it was a friendly or not. Cantona’s frustration with everything that surrounded him that night, the game, the referee, the icy field of play, swamped him. He took off his jersey and threw it towards his coach. Émile still pleads: ‘It was just a misunderstanding that was blown out of proportion.’ But millions were watching. Cantona was kicking a ball, or attempting to do so, to help raise money for widows and orphans. To him, however, at that moment, nothing mattered but a game of football, and an overwhelming feeling of injustice. ‘I tell you what,’ Gérard Houllier said in one of our conversations, ‘when we coaches had to referee training games, and made a wrong decision, oh my god, Éric wasn’t too pleased. In fact, we’d be looking for someone else to pass the whistle to!’

In no way did Cantona intend to demean the occasion. He had been wronged, and reacted without thinking. The image of Cantona’s shirt lying on the frozen turf would remain as potent and enduring an emblem of Cantona’s flaws to the French public as the Crystal Palace kung-fu kick would to the English.

A fidgeting Bernard Tapie, who had hoped for a better return on his FF22m investment over the first six-and-a-half months of the season, spoke of an ‘inqualifiable [indefensible]’ act, and helpfully suggested that ‘if we need to, we’ll put him in a psychiatric hospital’. The honeymoon had long been over between the two men; the chairman’s condemnation consummated the divorce. Michel Hidalgo, with some courage, went over the top to defend Éric: it was ‘neither an affair of state, nor a public affair’, he said, talking to everyone and no one in particular. The audience had already left. Where was Éric?

Cantona

Cantona