- Home

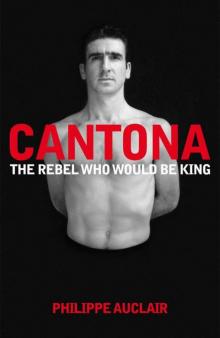

- Auclair, Philippe

Cantona Page 18

Cantona Read online

Page 18

First, Rennes ran out 2–1 winners at the Stade des Costières. Then Toulon blitzed the toothless Crocodiles 5–0. Caen inflicted on them their second home defeat in a row (0–1). Metz joined in the slaughter with a 4–0 win that didn’t flatter the hosts. Fourteen goals conceded in five games, one scored and no points: Nîmes were heading for the drop at this rate. It mattered not one jot that Cantona showed exceptional form when playing for his country; it merely substantiated the sceptics’ view that having Éric in your side was like having two coins in your pocket. When Platini flipped one of them, it landed on heads every time, whereas Mézy could only spin a dud.

On 20 November France established a new record in the history of the European Championship of Nations by winning their eighth and final qualifying match (their nineteenth undefeated game in a row – another record), to finish their campaign with sixteen points out of sixteen. In the absence of the suspended Papin, Éric had dazzled against Iceland in Reykjavik, revelling in the role of centre-forward in an ultra-attacking 4-2-4 formation. Two goals – one header from six yards, and a short-range shot following a superb one-two with PSG winger Amara Simba – rewarded one of his most devastating displays for the national team. A radiant Platini told the press how Éric ‘sees things more quickly than the others, understands them more quickly . . . He’s a very intelligent guy.’ This was some praise, coming as it did from a supreme master of the game’s geometry, Juve’s greatest-ever number 10. Cantona found it almost overwhelming. ‘This is the most beautiful compliment you can pay to a football player,’ he said. ‘The beautiful game recognized by someone who knows what he’s talking about . . . It gives me incredible pleasure. These few words are more important than thousands of critical comments.’

They also came at a time when Éric needed them the most. While on a short break in the walled city of Carcassone, he had just learnt that his adored grandfather Joseph had passed away. It was a bitter sea that lapped on the Côte Bleue from then onwards. One by one, the threads that bound him to his Arcadian youth were cut away from him. As he told his biographer Pierre-Louis Basse, ‘I should never have left the world of children.’ Cantona’s neverland is inhabited by many.

Éric, who had hidden his grief from all except those closest to him, still had to explain why he showed two faces to the world. ‘At Nîmes,’ he said, ‘it’s a different problem. It’s a team of youngsters who have great qualities, but who are still finding their way in the first division. With the national team, we didn’t reach that level in one day. We needed time. It’ll be the same with Nîmes.’ Time? But who was willing to give him time? It was so much easier to shoot him down. How did he feel about that? ‘Criticisms hurt,’ he admitted. ‘But nobody has succeeded or will succeed in killing me. Nobody.’

Then, during an otherwise uneventful, scrappy 1–1 home draw with St Étienne, on 7 December, Cantona committed suicide on national television. ‘He was fouled,’ recalled Henri Émile. ‘No free kick was given. He turned towards the referee and complained. The referee gave him a lecture. The game went on. Soon afterwards, he was fouled again. Still no free kick [in Émile’s view, because of the argument he had just had with the official]. He took the ball, threw it at the ref, and went to the dressing-room without even looking back.’

The referee, one M. Blouet, was made to look rather ridiculous as he brandished a red card at the departing player, standing straight-backed in his black shorts. Éric confided to a journalist: ‘It’s me, so, people will talk about it for two or three days. Then things will calm down. Time should be given the time to work . . .’ How misguided he was. Time was precisely what no one in the game’s establishment was willing to give him. Cantona was hauled in front of the FA’s disciplinary committee. He apologized for his action, and requested to be treated like any other player, expecting the customary two-game ban which punished any misdemeanour of this kind. But the response of the panel chairman Jacques Riolacci cut him to the quick. The apparatchik handed out a four-match suspension, adding, unforgivably: ‘You can’t be judged like any other player. Behind you is a trail which smells of sulphur. Anything can be expected from an individualist like you.’

Riolacci, who had been in place since 1969 and, at the time of writing, still held the post of chief prosecutor at the Ligue de Football Professionnel, was startled by Cantona’s reaction to his comments. Éric walked up to every member of the commission and repeated the same word: ‘Idiot!’ and left the room. The original punishment was extended to two months. That would teach him. Riolacci felt compelled to tell Agence France-Presse: ‘This is a striking summing-up of the character of a boy who has chosen to marginalize himself, and whom no one can channel.’

Reprehensible as Cantona’s behaviour had been, nothing could justify the harshness of the verdict and, especially, the condescending tone of the judge’s statement. If Éric wanted proof that he’d been tried for being Cantona, and not for what he’d done, he had it. They couldn’t quite push him off the cliff. So he jumped, and announced his retirement from football. Éric Cantona died for the first time on 12 December 1991.

‘To move away, to change clubs and horizons wasn’t something that worried me. I loved it,’ he said shortly after his second coming to Marseille. He may well have felt that way. But I was struck by one of Éric’s assertions that, when looked at more closely, made no real sense – certainly not when he talked to Laurent Moisset in 1990. Éric kept referring to his urge for constant change. ‘I need to feel good in a club,’ he said. ‘With everyone. To have clear, untwisted relationships. Maybe that’s why my adventures have been short-lived in some clubs. When you arrive, when you’re at the stage of discovery, you tell yourself, “Everything is going to be just fine.” Everything’s beautiful. As time goes by, sometimes, you realize it’s the other way round. It’s better to leave.’ True, at the age of 24, Cantona had played for five professional clubs already, and would join a sixth (Nîmes) a year hence. Howard Wilkinson would often refer to Cantona’s nomadism to support his claim that Éric’s departure from Leeds fitted a pattern of chronic instability rooted in the player’s character, not caused by the circumstances he found himself in. In 2009 this shuffling of clubs would not be deemed exceptional, especially as three of Éric’s moves were loans, not straight transfers. But nineteen years ago, when many footballers wore the same jersey for over a decade, Éric’s zig-zagging trajectory jarred with the commonly held view that a player ought to ‘bed himself in’ to succeed.

Wilkinson’s view (not so much an opinion as a consensus within football) superficially held water – until one realized that, contrary to his legend, Cantona had only instigated one of his moves, when he felt, not unreasonably, that Auxerre had become too small for him, and decided to join OM. As he said a few months after returning to the city of his birth in 1988, ‘I’d rather try to be good with the strong than bad with the weak.’ But his other clubs? Roux and Herbet had plotted his stay at Martigues. Tapie had sent him to Bordeaux, and didn’t want him back when the loan expired, which had enabled Éric to attempt the impossible with Stéphane Paille at Montpellier. And Cantona only sought to leave Marseille for good once his ostracism by Raymond Goethals had effectively erased his name from the club’s books. Was Éric deluding himself, or – which makes more sense to me – was he claiming a kind of freedom he aspired to, but which the football world couldn’t grant him?

How tempting it was to portray himself as a bird going from branch to branch on a whim, a butterfly tasting flower after flower, and how convenient it was for others to take this claim at face value, when the truth was that Cantona’s masters had disposed of him as a ‘piece of merchandise’, as he admitted to Moisset, but ‘a piece of merchandise who is asked what his opinion is’.

Éric was a vagabond, at least by the standards of his time, but a vagabond who had been shown the door. Sometimes, as in Martigues and Montpellier, this suited his own aspirations, and he could convince himself that he alone had written these new chapters in h

is story. During his time at the Bataillon de Joinville, his colonel had sent Cantona to load bags of potatoes a long way away from the barracks in order to avoid a conflagration. Éric had won. But at Marseille, he dangled from a string in Tapie’s puppet show. He referred to Tapie as ‘a manipulator’. Is it any wonder that he despised him so?

This is another leitmotiv in the Cantona canon: Éric’s peaks always coincided with the presence of a father figure at his side, a benign authority, but an authority nonetheless. Auxerre teammates like Prunier, Dutruel and Mazzolini used to tease him by exclaiming: ‘You are Roux’s son!’ Yet he professed to hate any kind of regimentation. Following one’s impulses sounded more poetic than following somebody else’s orders. Think of what Rimbaud might have said to Tapie. But a poet only needs pen and paper to be a poet, whereas a footballer needs a club to become the artist of Éric’s dreams. Players exist only in the present, even now that ‘immortal’ avatars of their selves are preserved through digitization, like figures in a stained-glass window. Despite what Éric repeated time and again, he couldn’t be satisfied with going back to the street and juggling balls made of rags in the dust. To be a rebel, Cantona had to sign a contract first. To reclaim the joy which filled him in his youth, he had to accept the obligations of a pro. At times, he must have felt as if he were kicking the ball in the courtyard of a prison. Erik Bielderman’s words keep coming back to me: ‘Cantona sees everything in black and white, but no one is greyer than him.’

True, Éric always wanted to ‘play’. And when you play, you don’t cheat. Cheating is for those who pursue an ulterior motive, be it financial reward or power. But Éric’s pursuit of purity was hampered by his excelling in a sport where transfers (aren’t prisoners ‘transferred’ from jail to jail?) were handed out like sentences in court, and where calculation, in the form of tactical organization, is crucial to success on the field. Who does he consider to be the greatest player ever? Diego Maradona, of course, the only footballer who authored the triumphs of his teams, with Napoli and Argentina, and earned the right to sign his name in a corner of their masterpieces. Which team does he place above any other? The Netherlands led by Johann Cruyff in the first half of the 1970s, famous for their ‘total football’, which, at its most beguiling, looked like collective improvisation. Magnificent aberrations both.

Éric never reached their heights, but could at least cloak himself in the garb of a traveller, the wandering footballer whom nothing or nobody could tie down. He never did anything to discourage the myth-makers; in fact, he helped them write the legend. I’m the one who walks away, he told them, the hobo who answers the call of the road. As these confessions (or delusions) gave credence to the story journalists wanted to write, and their audiences to read, they were added to an almighty mess of half-truths and plain fabrications. The king’s palace sometimes looked like a junk shop.

Then again, football can also be a redeemer. I’m thinking of Marco Tardelli running back to the halfway line after scoring Italy’s last goal in the 1982 World Cup final, possibly the most exhilarating celebration ever seen on such a stage. What was the man-child screaming, as his whole body shook with the realization of what he had just done? ‘Tar-del-li!’ That’s what – just like every schoolboy who has shouted his own name after imagining he had scored a World Cup-winning goal. I hope I can be forgiven this truism: in the chest of every sportsman beats the heart of a child. Cantona’s pulsed more quickly than most and that heart, at least, was never tamed.

8

Éric salutes the Parisian crowd.

DECEMBER 1991:

THE FIRST SUICIDE ATTEMPT

‘It was over – but I wouldn’t have died. I had the privilege to be a witness to my own funeral. That’s everyone’s dream: to know what will be said, how people will react.’

(Here’s a game every child has played: let’s pretend.

Let’s pretend that the Japanese football season didn’t end in March that year: Éric Cantona might never have come to England.

Let’s pretend that a ski-lift did not stop 30 metres above the slopes of Val d’Isère in late December 1991: Éric Cantona might never have played for Leeds and Manchester United.

And now, let’s see what really happened.)

Éric’s decision to retire was made public in a statement to Agence France-Presse on the day the very first web page went ‘live’ on the internet: Thursday 12 December 1991, forty-eight hours after he had confronted the French FA’s disciplinary commission, flanked by his manager and chairman Michel Mézy. Cantona had sent out invitations to his own wedding after Isabelle and he had tied the knot, but he made sure on this occasion that everyone was informed of his death as a footballer in good time. Whether he had committed suicide or been assassinated by the game’s establishment depends on the degree of authorship one is willing to grant Éric for his career. I would lean towards the first interpretation, as there was no shortage of important figures throughout the game that were dismayed by the announcement and expressed their support for the outcast, including some at the very top of France’s hierarchy. Michel Platini had long feared that Cantona’s quixotic move to Nîmes would end in tears and had sounded out Liverpool manager Graeme Souness as early as the beginning of November, on the occasion of a UEFA Cup tie between the Reds and Auxerre. Would he consider making a bid for Éric at some point?

That brief exchange (which Souness owned up to many years later) led to nothing, of course, but showed that the French manager had already thought of England as the country of Cantona’s rebirth. Without Éric, Les Bleus would have struggled to qualify for Euro 92, and would find it far more difficult to make an impression in the tournament proper. Their manager set the wheels in motion as soon as it appeared that Cantona was lost to football. He first tried to make Éric change his mind, without success. Then, unbeknown to Cantona, Platini and Gérard Houllier used their contacts within the English game to reach first base in the strange game of rounders Éric’s rescue proved to be.

Eulogies poured in, as numerous as expressions of disbelief. One of his France teammates, goalkeeper Gilles Rousset, made this comment: ‘Football has lost a great player. But life has just gained a super guy . . .’ Cantona’s brother-in-law Bernard Ferrer expressed his incredulity: ‘He’ll come back. He loves his job.’ At Nîmes, all those involved in the life of the club closed ranks around Éric: Bousquet, Mézy’ the new skipper too, Jean-Claude Lemoult – remember him? The same Lemoult at whom Cantona had thrown a shoe in Montpellier – who read out a very emotional statement written by the playing staff: ‘Éric had nothing but friends here and hasn’t lost them. We want him to know that he’ll be able to find us any time he needs us. And that we’ll always be here, with him, if, one day, he feels like playing again, if he changes his mind.’

But Cantona, touched as he was by the expressions of sympathy that came his way, had no intention of changing his mind. His decision was ‘irrevocable’. If it hadn’t been for Nîmes, a city he loved, and Michel Mézy, one of his most cherished friends, he said, ‘I’d have chucked everything away, I’d have left [already]. I wouldn’t have played football.’ Why he had come to such a dramatic conclusion he didn’t explain in more detail until a month-and-a-half later, when it looked as if he was about to settle at Sheffield Wednesday. ‘I decided to stop because there had been many things which had been pissing me off for a while,’ he told a French reporter. ‘Many things I loved, too. But it had been going on for a long time. I’ve never said that I was in a milieu where I felt at ease, ever since I started playing [professionally]. But because I love the game, I decided to ignore what didn’t agree with me. The decision of the disciplinary commission was the last straw . . .’ Why hadn’t he decided to pack up playing earlier, then, when Bernard Tapie and Raymond Goethals had done everything in their power to make him lose his hunger for football at Marseille? ‘That would have been too easy. I wasn’t playing. I’m a winner, not a loser. I’d just played a great game with the French team [the 3–1

win against Iceland on 20 November, in which he scored twice], it was the right time. It’s precisely when everything goes wrong that you must find the strength to go on.’

To start with, ‘irrevocable’ seemed to mean just that, despite the dramatic consequences tearing up his contract with Les Crocodiles would have on his family’s future. Mézy, deeply moved, explained that the club had accepted the compensation plan that Cantona had put forward – which was substantial, as there were still two-and-a-half years of his contract to run. Fully aware of the difficulties Éric would face in paying the equivalent of over £1m, Nîmes generously proposed a ‘sabbatical’; but Éric would have none of that. His heart told him that agreeing to an extended holiday from football would be akin to lying to himself and to a club he had a great deal of affection for, and his pride baulked at the idea that he couldn’t be a man of his word. This didn’t prevent Mézy’s conciliatory attitude from being subjected to fierce criticism, as Nîmes didn’t have the resources to let Éric go and forget about the money they had invested in him. Legally and morally, Cantona himself was personally responsible for the whole of that sum, and paying it would bankrupt him, despite the huge salaries he had received since arriving at OM in 1988. The building contractor he had instructed to build a house on the outskirts of Nîmes politely asked if he would be able to meet the costs. A few weeks later, soon after arriving in Sheffield, he told a France Football journalist that he had ‘a lot of money put aside’. That much was true, but there would have been very little left of it had he had to buy back his contract. Maybe his wish ‘to be poor’, which had shocked so many when he expressed it four years earlier, was not just the idle, irresponsible talk of a born provocateur after all.

Cantona

Cantona