- Home

- Auclair, Philippe

Cantona Page 23

Cantona Read online

Page 23

The match itself was a mere sideshow to the triumphant parade the following morning. An estimated 150,000 people – over one-fifth of the city’s entire population – lined the streets where the team’s open-top bus proceeded at a snail’s pace. The closer it got to the Art Gallery, where a temporary stand had been erected, the thicker the crowd, the louder the songs, until, finally, one by one, the champions were introduced to their fans. Huge cheers greeted the appearance of Strachan and Wilkinson, but reached a fortissimo when Éric’s turn came to salute the multitude. The now familiar chant of ‘Ooh-ah, Cantona, say ooh-ah Cantona!’ filled the Headrow. Éric, stunned, raised his arms and clapped. Who was applauding who? Who was the star, who was the admirer?

Later that evening, the heroes gathered with 400 guests in Eiland Road’s banqueting suite, where they received their championship medals from the hands of Leeds chairman Leslie Silver. Cantona, sporting a psychedelic multi-coloured shirt’, listened to the speeches, smiling when the Posh editor Chris Bye opened his allocution with a few words in French. Cantona’s teammates didn’t mind the praise lavished on the single member of their squad who didn’t carry a British passport, even though Éric had taken part in only fifteen of forty-two league games (nine as a sub) and scored the same number of goals as left-back Tony Dorigo: three, which gave him equal eighth place in Leeds’s scoring charts. Most of them agreed with journalist Mark Dexter, who wrote that ‘Wilkinson’s best move of the campaign [had been] the signing of Éric Cantona on loan’. His presence had nourished the belief, both on the terraces and on the pitch, that, after eighteen trophy-less seasons, this could be Leeds’ year.

Wilkinson’s attitude was more ambivalent. Feted as ‘the future of English football’ (both a bleak prospect and a less-than-prescient prediction, as no other English manager has lifted the championship trophy since he did), he revelled in the plaudits he received at the hour of his greatest achievement, but was puzzled by the importance attached to Éric’s role in the conquest of the title. Less charitably minded observers suggested that Wilkinson resented having someone else steal his thunder. Had he not been the director, and Éric a mere extra? For the time being, with a city ‘living on champagne’ (as a player’s wife put it), and Leeds about to take part in their first European Cup since a bitter loss to Bayern Munich in the 1975 final, such interrogations could be left aside. They made no sense for Cantona himself. The French public struggled to understand how he had accepted a glorified substitute’s role with good grace at Leeds when he wouldn’t have (and didn’t) at Olympique Marseille, for example. The answer was simple. ‘I have always been implicated in the adventure of Leeds,’ he explained shortly before the start of Euro 92. ‘The manager always trusted me. He brought me in little by little. He didn’t want to “burn” me. People managed to make me understand the reality of English football, the life of the club . . . Remember that I had so many things to discover.’

To him, England had represented a means to an end – literally: the end of a potentially catastrophic dispute with Nîmes, which could have left him penniless. Four months on, not only had he settled that matter once and for all, but also discovered a country in which his ‘difference’ was cherished. ‘If things had not worked out at Eiland Road, I would have quit the game,’ he assured Mike Casey in the second (and last) of his heart-to-hearts with the British press. But the Leeds manager and players ‘have taken me at my face value and ignored the stories about me being a bad boy. The fans too have made me so very, very welcome. I love them. I’m flattered by the way they have treated me. The English have a great sense of respect for people and that has been very helpful to me. Despite the language barrier, I know they like me. And that feeling is mutual.’

On 5 May, a couple of days after sending his love letter to the Post readers, Éric packed his bags and made his way back to Paris, where Michel Platini and his squad were waiting for him. The first French player to receive a championship winner’s medal in England now had to get himself fit and ready for Euro 92 (shedding the four kilos he had put on in a single week of celebrations in Yorkshire would be a start). Cantona’s progress in the English league had been documented in great detail by the French media, but Wilkinson’s cautious handling (if not wariness) of his charge had not gone unnoticed either. Not everyone was convinced that a reformed character would step off the plane at Roissy. There would be trouble ahead, they said, in which they erred. What lay ahead was in some ways more hurtful than trouble: disappointment.

Researching this book entailed going through hundreds of match reports and viewing hours upon hours of tapes of games that have been forgotten, and not without reason. It’s not paying a great compliment to the British press to say that, nine times out of ten, reading the account of a match brought more reward than watching it. It is easy to forget the rut into which English football had fallen at the time Éric Cantona arrived at Eiland Road. The post-Heysel exile from European competitions had made English football fold back into the worst of itself, a perverse mixture of fear – of the outsider, the foreigner, the eccentric – and glorification of ‘manly’ virtues in which the detached observer could see little but crudeness and brutality. What happened on the pitch mirrored what took place in the stands. Football of the late 1980s and early 1990s was a drab, sometimes vicious affair. There was no shortage of hard-working, hard-tackling, box-to-box one-footed midfielders. In almost every team could be found what is regarded as a ‘typical’, or ‘old-fashioned’ centre-forward, all forehead and elbows. Some were fine pros, the heirs of Nat Lofthouse, keepers of a respected tradition. Éric’s Leeds teammate Lee Chapman belonged to that family; but too many others were bullies who would have been refereed out of the game on the Continent. Central defenders hoofed the ball away from the danger zone with the blessing of their coaches. Everyone was running at a hundred miles an hour, saturating their jerseys with honest sweat, kicking and being kicked, negating what skill they might have had in the relentless pursuit of victory.

More delicate birds like Glenn Hoddle and Chris Waddle had flown south, to Monaco and Marseilles respectively, and both had been welcome in the country Cantona had vowed never to play in again. Clive Allen, Trevor Steven, Ray Wilkins, Graham Rix and Mark Hateley also flourished in France. In any case, at least since Stanley Matthews’ retirement, and despite the brief regency of gifted rogues à la Rodney Marsh and Frank Worthington in the early 1970s, dashers had always been thin on the ground in England. The few who had surfaced had rarely been trusted by managers influenced by the noxious theories of the long-ball merchants who wielded a great deal of influence within the FA. The name of Charles Reep should still send shivers down the spine of anyone who cares about football. In fact, more often than not, the entertainers came from Scotland, the land of the passing game, Ulster or the Republic: Kenny Dalglish, George Best, Liam Brady. Those who did not frequently ended up on the scrapheap, like the tragic Robin Friday, hacked to oblivion after shining so brightly, so briefly, for Reading FC.

In the eight years between the butchery of Heysel and Manchester United’s first championship title since 1967, English football seemed to be played in the deep of winter, on windswept, rain-soaked fields of mud. It could still hold a visceral appeal for the Saturday crowds; but these crowds were dwindling, despite the cheapness of tickets, and not just because the so-called ordinary fans wanted to avoid trouble. The poison of hooliganism was a symptom, not necessarily a cause, of the game’s sorry decline. It was Cantona’s paradoxical luck that he drifted to England precisely when the game he loved was played there in an environment and a fashion that ran against his deepest-held convictions and feelings. Should he fail, it would be a confirmation that a player for whom self-expression was paramount had better pursue personal fulfilment elsewhere; the failure would not necessarily be his. Should he succeed, he would become Éric Cantona as England remembers him.

Of the twenty-two teams which then comprised the old first division, only three or four could claim to play e

ntertaining football. Spurs clung on to their aristocratic reputation with varying degrees of success or justification. Ron Atkinson’s Aston Villa, infuriatingly inconsistent though they were, at least put on a decent show for their fans. Norwich’s combination play, with its simple elegance, its emphasis on passing to feet in neat triangles, could remind a Continental connoisseur of another team clad in yellow, the ‘canaries’ of FC Nantes. Alex Ferguson held on to his belief in the more expressive, more vibrant brand of football that had brought him success with Aberdeen – but with players who did not quite possess the technical ability required to fulfil his ambitions. And that’s about it. Nottingham Forest was fast becoming a shadow of its former, admirable self, and so was Liverpool, who could still summon some of their old verve, but too fleetingly to equal their previous incarnations. Sheffield Wednesday held promise, but did not have the financial resources to rise above the fray for long. This is no exaggeration. Watching English football in 1992 might have been exciting – for some – but it certainly wasn’t pretty.

There is little to indicate that Cantona himself was aware of Leeds’ role of villain in the pantomime of English football. England was not his spiritual homeland; Brazil, yes, where, to him, ‘passing the ball [was] like offering a gift’, the Netherlands too, whom he had wished to beat France when they met in a crucial World Cup qualifier in 1981. What little English football was shown on French television when he grew up (and believe me, it was very little) came in infuriatingly short snippets of Liverpool cutting the opposition to shreds in the Sunday evening sports programme. From time to time, before 1985, a European game featuring an English team might dislodge a TV drama from its evening slot, and a great deal was made of the ritual known as the FA Cup final, in which many saw the sporting equivalent of a coronation, an arcane, quasi-mystical ceremonial so far removed from our own experience that the less we understood it, the more pleasure we derived from its pomp and circumstance. In international tournaments, England kept on under-performing with bewildering consistency; in fact, when Éric signed his first professional forms for Auxerre, in 1986, the heirs of Bobby Moore had not been in serious contention for a major title since the 1970 World Cup – when Cantona was four years old.

True Anglophiles like Gérard Houllier, the exceptions rather than the rule, tended to come from the north of France, where strong links had been forged between footballing cities from each side of the Channel. My home team, Le Havre Athletic Club, which had borrowed its colours from Oxford and Cambridge universities, had taken part in semi-serious summer tournaments with the likes of Portsmouth and Southampton in the 1960s. It felt natural to confess an allegiance to, say, Peter Osgood’s Chelsea, just as it felt natural to listen to The Kinks, The Clash or Doctor Feelgood. The more adventurous would book a trip on the ferry to stand in the terraces of Fratton Park or The Dell, or listen to Ducks DeLuxe at the Hope and Anchor, but such visitors were few, and Cantona certainly didn’t belong to that micro-culture. He himself had trodden on English soil just once before flying to Sheffield. That was in 1988, when he played that splendid game against the England under-21s at Highbury. English football still carried an aura, now tinged with real menace after its travelling supporters’ innumerable excesses. Our national team invariably lost against the rosbifs (our 1986 campaign, which saw Les Bleus play one of the greatest games of this or any tournament, a 1–1 draw with Brazil, had started with their customary defeat against Bryan Robson’s team), and French clubs rarely fared better when drawn against the English in Europe.

The fanciful souls who had crossed the Channel to seek some kind of footballing glory before Cantona could be counted on two fingers. In the early years of the twentieth century, a goalkeeper named Georges Crozier had been employed by Fulham – but he was an eccentric rather than a pioneer. More recently, the failure of Didier Six at Aston Villa exemplified the irreducibility of our footballing differences. A strong, speedy winger of established international pedigree (he played in the 1982 World Cup semi-final), Six could cross the ball beautifully from both flanks. His direct, determined play should have suited the English game; instead of which, following a handful of promising performances, he foundered and left after a single season (1984–85). Platini and Houllier knew this, but, partly out of desperation, they trusted their instincts, and their instincts told them that no clear alternative presented itself to save the career of the most gifted French player of his time, in their eyes the only one who could fill the huge void left by the final eclipse of the 1978–86 golden generation. England was the choice of a gambler down to his last few chips; the last-chance saloon.

10

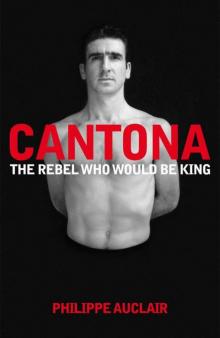

The acrobat at work: at Clairefontaine with the French squad.

FAREWELL TO DREAMS:

EURO 92 AND EXIT FROM LEEDS

The 1992 European Championships are now remembered for the astonishing triumph of Denmark, and little else. The Danes had been drafted in at the eleventh hour (nine days before the start of the competition, to be precise) to replace the team they had finished behind in their qualifying pool. The soon-to-be ‘former Yugoslavia’,23 then torn apart by civil war, had been excluded by UEFA in accordance with United Nations resolution no. 757. Denmark, perennial makeweights of international competitions (one participation in the final phase of the World Cup until then), then qualified ahead of France and England in the Euro 92’s group phase before dispatching Dennis Bergkamp’s Netherlands and Jürgen Klinsmann’s Germany en route to the biggest shock witnessed in a major tournament since Uruguay beat Brazil 2–1 at the Estádio do Maracanã in 1950. The Danish squad’s preparation had been minimal, so much so that many of the players were said (wrongly, it seems) to have cut their summer holidays short to rejoin the squad in Sweden, where the championships took place. Their coach, Richard Møller Nielsen, had stayed at home: there was a new kitchen to be installed, apparently. Michael Laudrup, the undoubted star of a team in which there weren’t many – not yet, anyway – had announced his retirement shortly before UEFA informed the Danes that they had qualified by default. The rank outsiders dropped their buckets and spades and, with all the odds stacked against them, had their day in the sun. It made for a heartwarming story, which, unfortunately, the football played in the competition didn’t live up to. Denmark, with an exceptional Peter Schmeichel in goal, set out to nullify what little threat their opponents dared to pose, and succeeded beyond their wildest expectations, while their Viking-helmeted supporters popularized face-painting and drank Sweden dry. Goals were scored at the pitifully low rate of 2.13 per game, an average inferior to that of the most dismal World Cup of modern times, the Italian 1990 Mondiale (2.21). And for the French, it was even more miserable than that.

Les Bleus hadn’t taken part in a major tournament for six years, but made most observers’ short list of favourites. No other team had ever sailed through the qualifiers with such ease: eight games, eight victories, a record that still stands. Before England had prevailed 2–0 at Wembley in February, Platini’s men had remained undefeated for over two years. A couple of hiccups against Belgium (3–3) and Switzerland (1–2 in Lausanne) prior to the championships didn’t worry their supporters unduly, as Michel Platini had used these friendlies to try out new players and tinker with tactical formations (no less than six substitutes had been introduced against the Swiss, another European record in internationals for Platini). When, five days before the start of the tournament, France drew their last warm-up game 1–1 with the Netherlands, the satisfaction of having contained a redoubtable opponent obscured the negativity of the performance. It was almost universally thought that, once the tinkering had stopped, the true visage of France would appear.

Sadly, it was a sullen face that Platini’s team showed to the rest of Europe. This most inventive of players adopted a negative strategy that would have been anathema to his mentor Michel Hidalgo. For France’s inaugural game against Sweden, Platini ditched the 4-3-3 that had served him so well during the pre-tournament phase in favour of a lopsided system

in which Cantona was required to play in a withdrawn position behind Jean-Pierre Papin, and Pascal Vahirua alone provided a measure of width. The Swedes were well worth the 1–0 lead they held at half-time, and were entitled to feel disappointed when JPP equalized from fifteen yards on the hour. Éric had been at best subdued, at worst transparent. Some wondered whether the calmer, more mature Cantona who had emerged from four tremendously successful months in England hadn’t lost some of his old bite. Judging by his next game, they might well have had a point.

The ninety minutes of that goalless draw between England and France must rank among the most tedious ever suffered by the fans of both teams. Platini asked his veteran midfielder Luis Fernandez to drop so deep that Les Bleus took the shape of an inverted pyramid, a grim 5-3-2 in which Cantona and Papin, with no support to speak of, watched the ball being tackled to and fro in midfield by the likes of Carlton Palmer and Didier Deschamps. Come the end of the most depressing anticlimax of the competition, Graham Taylor’s and Michel Platini’s teams found themselves with two points from two games – in other words, perilously close to the elimination their displays so far merited. And to every neutral’s satisfaction, they exited the tournament three days later, Sweden taking care of England by 2 goals to 1 and Denmark, astonishingly, seeing off France by an identical score-line. No French or English player featured in the Group 1 XI selected by the French press after three games. Cantona? Not a single goal. No assist. His only contribution of note had been in France’s equalizer against Denmark, when his cross from the right was controlled, then backheeled by Jean-Philippe Durand for the on-rushing Papin. A few hours after their defeat, a lugubrious French team boarded a private charter plane and left Sweden in silence.

Cantona

Cantona