- Home

- Auclair, Philippe

Cantona Page 6

Cantona Read online

Page 6

In January 1984 the French juniors were invited to take part in a six-team indoor tournament in Leningrad. Éric had been made welcome in this set-up. His head coach, the late Gaby Robert, enjoyed a very close relationship with him, for Robert was a Marseillais too, a jovial, kind-hearted man who knew when to shrug his shoulders or look the other way, and when to have a heart-to-heart with the ‘unmanageable’ youngster he treated like a son. Robert, however, found himself at the centre of another potential Cold War crisis when Éric, incensed by a refereeing decision, spat in the face of the Soviet official. The official in question was a colonel in the Red Army, who sent him off on the spot in front of an aghast French delegation. Diplomats did what they had to do. Nothing came of it, somehow, and Éric flew home with his teammates; but word of his exploits had already been passed on to the Auxerre manager. Roux quietly dropped him from the first team (with whom he had played two games already, as we’ve seen), and started to work on his next move.

Éric turned eighteen in May of 1984. For all Frenchmen of his generation, reaching that age meant a call-up to the army. Then again, ‘call-up’ signified many things. For most, twelve months of tedium, loneliness and ritual humiliation in a remote provincial town or, if you were particularly unlucky, in Germany. A few weeks of drill, then the mind-numbing routine of life in the barracks – dodging ill-tempered and foul-mouthed adjutants during the day, downing Kronenbourg beer and playing table football, pinball or billiards in the evening. Students, who benefited from a suspended sentence (conscription could be postponed until they had completed their degree, up to the age of twenty-two), hoped for a posting abroad. One of my friends ended up promoting French cinema on behalf of French consular services in Ottawa, which should tell you everything about piston, France’s answer to the Anglo-Saxon old-boy network. Elite sportsmen dreamed of joining the Bataillon de Joinville, an army in shorts and tracksuits that never saw a gun, and was expected to carry the flag in international competitions instead.

The Bataillon had, shall we say, something of a reputation. Joinville was conveniently close to Paris, and one-night desertions were tolerated by the military. Roux, an expert in the piston system, usually preferred to have his young players assigned to the local gendarmerie. Conscript footballers were allowed to return to their club for the weekend’s games as a rule; should they become gendarmes in Auxerre or Chablis, they would also be able to attend a number of training sessions – and Roux could keep an eye on them, of course. But is a gendarme a soldier? Not quite. Perhaps misguidedly, the Auxerre manager thought that his rebellious Marseillais would encounter sterner discipline in the Bataillon, and phoned his friend Joseph Mercier – who happened to be the man in charge of this unit’s footballing squad. Mercier, who is now well into his eighties, chuckled when I asked him why Roux had made an exception to his rule in Éric’s case. ‘Oh, Guy always hid his boys at the gendarmerie! But Cantona posed a few problems to Auxerre, because of his well-defined personality.’ (Mercier is a master of the understatement.) ‘He told me, “I’m sending you a top lad” . . . that made me laugh. I knew exactly why he was doing this. To have the lad knocked into shape.’

When I put this version of events to Roux, I was hit by a barrage of not entirely convincing incredulity. ‘I had no choice,’ he blustered. ‘Éric was already an international footballer with the under-21s [not quite: with the under-19s, but you get Roux’s point]. He had to go to Joinville!’ I could imagine Mercier’s chuckle in the background. Whatever the truth may be, the experience was only a qualified success. The little control Cantona may have had over the wilder side of his character was lustily relinquished. ‘We burned what was left of our adolescence,’ Éric told Pierre-Louis Basse. This ‘we’ refers to Éric and Bernard ‘Nino’ Ferrer, who, though he was two-and-a-half years older, had been conscripted at the same time: Roux obviously thought that Éric needed company. ‘We prepared ourselves to spend a year sleeping during the day, and having fun at night’ – which is precisely what they did.

Their behaviour would have shocked a hussar of Napoleon’s army. Mercier, a prudent man, had asked to be relieved of his duties shortly after Éric’s arrival at the Bataillon, and only supervised a handful of international games, including one against West Germany, before passing on the baton to Jacky Braun. Braun declined to be interviewed for this book, as he would ‘only have unpleasant things to say’ about Cantona. A pity. He might have shed some light on an eventful tour of Gabon which saw Éric ‘flirt with death’, that is: experience a very nasty trip after smoking the local dope with strangers in the capital Libreville. ‘Fear quickly took the place of curiosity,’ he wrote in his autobiography. ‘The fear of dying. [ . . .] I had been looking for artificial paradises, but it is anguish that was waiting for me at the end of such a journey. One does not resist the attraction of the forbidden fruit . . .’ Tellingly, a rite of passage had become a brush with the Grim Reaper. Éric never did things by halves.

Cantona’s understanding of the logic that led to his being assigned to Joinville differed from Mercier’s and Roux’s. To him, his mentor had connived with an accomplice to give him a chance to sow his wild oats before he settled down with a fiancée or a bride – like most professional footballers do at a very young age – to a life of ‘sleeping, eating, playing, travelling without having the time to comprehend the countries [they] go through’. It’s hard to see in this anything but an attempt to justify the recklessness of his behaviour at the time, which was exacerbated by his visceral rejection of any kind of institutional authority. He knew that Joinville conscripts enjoyed a privileged status. They could do pretty much as they pleased, and get away with acts of indiscipline that would have earned ordinary squaddies a few nights in jail. He exploited this leniency to the full. Roux, who paid weekly visits to the barracks, was appalled by what the colonel in charge of the Bataillon told him. A general had announced his intention to meet the flower of France’s youth; but Cantona had developed an aversion to shaving at the time, and looked like an extra from Papillon. Unfortunately, this particular soldier had very personal views on what constituted an order. His adjutant tried to cajole him into getting rid of his coal-dark stubble, but to no avail. The colonel didn’t fare any better. ‘I do not shave,’ was Cantona’s answer, each syllable of ‘‘Je-ne-me-ra-se-pas’ enunciated in a low, forbidding baritone. The officers relented. They put Éric in a lorry and sent him on an impromptu trip to Orléans, a hundred and fifty miles away, to collect bags of potatoes.

This chore must have felt like a victory, another white flag hoisted by the men in uniform. It is no wonder that Éric, unlike 99 per cent of his contemporaries, had fond memories of his time at the service of the nation. Five years later, he crossed Mercier’s path again, when Montpellier played a game in Châteauroux, to where the coach had retired. Coming out of the dressing-room, he recognized his benevolent manager, gave him a mock military salute and exclamed: ‘Ah, Monsieur Mercier, yes, sir!’ – in English. ‘The first thing I told my players,’ Mercier explained, ‘was – do not discuss a referee’s decisions more than a US Marine would discuss an officer’s order.’ Roux’s plan to have ‘the lad knocked into shape’ hadn’t quite worked as planned.

It hardly mattered, though. Right at the end of the season, as Auxerre were striving for a place in the UEFA Cup for the second time in their history,6 the uncontrollable Éric gave two magnificent demonstrations of what Roux does not hesitate to call his ‘genius’. The first of these was on 14 May 1985, in the antiquated décor of the Stade Robert-Diochon, in Rouen, nine days before Cantona’s nineteenth birthday, when he scored the first of his 23 league goals (in 81 appearances) for the Burgundy club. ‘It was a rotten game,’ says Roux. ‘My three ’keepers were unfit. In the end, [Joël] Bats played – but couldn’t kick the ball. It was pissing down. This is Rouen, the chamber-pot of France. Water everywhere. Over an hour had been played. Canto started from the middle of the pitch and ate everything: the puddles, the defenders, he left ever

ything behind, he munched the lot, and scored with a piledriver.’ Auxerre won 2–1, thanks to a complete unknown. Two weeks later, more drama, more Cantona.

Strasbourg this time, at the Stade de la Meinau. AJA need a single point to guarantee a place in Europe, and things aren’t going too well. ‘My son was studying there at the time,’ Roux says. ‘He’s listening to the game on the radio. We’re losing 1–0 at half-time. We’ve got to do something, I tell them, we’re not going to miss out on Europe like this! We were dead. I didn’t have a go at them, as I knew they couldn’t do more. Cantona said something like: “I’ll take care of it.” And he did. He took the ball in midfield. He pushed it once, and whacked the ball from the centre circle. Goal. 1–1, Auxerre is in the UEFA Cup.’ Cantona himself relived his equalizing goal with the clarity of a dream. No, he wasn’t in the centre circle – a little over 25 yards from his target. But as soon as he had received the ball in his own half (that much is true), he had known that something special, preordained (‘I’ve always felt I was watched over by something greater than me’) was about to happen. That was the day, 28 May 1985, on which an exceptional footballer emerged from the chrysalis. To think that, the day before the game – something that Guy Roux’s spies had failed to report – Éric, accompanied by his friend Nino (a nickname Bernard Ferrer owed to sharing a surname with one of France’s most popular sixties pop singers), had drifted from bar to bar, nightclub to nightclub, girl to girl, until four in the morning. To think that within a few weeks, the teenager would meet the woman who would anchor him at last. Cantona’s apprenticeship was over.

3

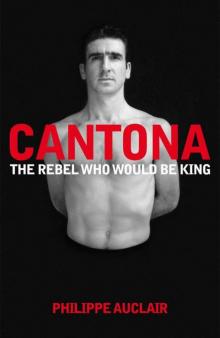

Cantona at Auxerre, May 1985.

AUXERRE:

THE PROFESSIONAL

For Nino Ferrer, the time to settle down to the life of ‘sleeping, eating, playing, travelling without having the time to comprehend the countries [footballers] go through’ came that summer, when he got married, at the age of twenty-one. Éric was one of the first names on his list of guests, naturally. At the wedding reception, his eyes fell on Nino’s sister Isabelle, whom he had already met, albeit fleetingly, when she had visited her brother in Chablis, where she could revise for her exams in peace.

Three years Éric’s elder, Isabelle could not have been further from the archetypal WAG, be it in looks or personality. When I met her more than twenty years later in Marseilles – she and Éric had been living apart for five years by then – she retained the charm and allure which had convinced Éric he had met the woman he wanted to grow old with. She came from a humble background not dissimilar to his, and spoke with the delightful southern lilt of the Provençal working class. She had been studying literature at the University of Aix-en-Provence and had done very well there, supporting herself by working as senior clerk in a supermarket. She was graced – le mot juste – with beautiful dark eyes and a sunny, yet slightly melancholy smile. She was no bimbo, but a very attractive young woman who was not afraid to let her heart rule her reason, as she showed when, after spending two weeks in Éric’s Auxerre flat, she jumped from the train taking her back to Provence to spend another couple of days with the man she loved. Thus was born the apocryphal tale of a near-mad Cantona forcing that same train to stop by jumping on the track in front of the locomotive. The truth was simpler, sweeter, and more fitting. She would be the discreet and faithful companion of Éric throughout the turmoil and the triumphs of his whole career; to borrow from Cantona’s favourite poet Arthur Rimbaud, she was the rock to which Éric could always moor his drunken boat. She asked me to withdraw much of what she told me from this book, and I have done so. Her memories are too raw, and what need is there to sharpen what pain they may carry for the sake of an anecdote or two? Still, Isabelle, whom I’ve always heard being talked about with affection, respect and even admiration, cannot remain a silent silhouette cut out from the backdrop of Éric’s melodrama. Her selfless love for her husband ennobled him, and I don’t believe you can tell a man’s story if you do not speak, even that briefly, about the woman he loved more than any other.

But settling down like his teammate Nino had done was not on Éric’s mind just yet, despite the passionate nature of his first real relationship. A footballer’s summer lasts but a few weeks: Éric had to go back to the training ground, Isabelle to her books, hundreds of miles away. Already disoriented by the violence of his feelings, and by the frustration of being so far from the one human being he wanted to be with, he also saw the beginning of his 1985–86 season ruined by a viral infection that kept him out of the first team from mid-August to early October – precisely at the time when Andrzej Szarmach’s departure meant that he could claim a place in the Auxerre forward line. Roux had promised to give him a string of games to establish himself, and was true to his word, but Éric, his mind elsewhere – in Provence – failed to capitalize on the chance he had been given. He didn’t score a single goal in the six games (one victory, two draws, three defeats) he could take part in before the virus struck him down; and when he had recovered his fitness, it was to find that another striker had claimed his spot in Roux’s first eleven: Roger Boli, brother of man-mountain Basile, a quick, clever centre-forward, whose goals had kick-started Auxerre’s stuttering season.

AJA won at Nice thanks to him, then recorded the most brilliant victory in their history by beating mighty AC Milan 3–1 in the first leg of the UEFA Cup’s first round. Boli had scored again, and Cantona found it hard to share fully in the joy of his teammates. What’s more, when he rejoined the team, on the occasion of the second leg, it was to be on the receiving end of a 3–0 drubbing. Any player would have suffered a blow to his pride in such circumstances; and Cantona’s pride was as strong a current in his character as insecurity, strong enough to flood him when so much in his life was already in a state of flux. Roux, who loved him and understood him better than any manager other than Alex Ferguson (some of Éric’s teammates openly teased him about his relationship with ‘Papa Roux’), was at pains to comprehend why the player who had lit up the end of the previous campaign had retreated into his shell. That is, until he was told by one of his many spies that Éric’s Renault 5 had been spotted on the motorway, heading towards Aix-en-Provence. ‘All my guys were stationed at toll-gates between Auxerre and Paris,’ he explained to me. ‘But it so happened that one of them had taken the place of someone who worked between Auxerre and Lyon, on one of these nights when Éric was driving south! I’d never have known about it otherwise.’ Roux asked for an explanation; Éric gave it to him. ‘I want to see her,’ he said. ‘It’s her I love.’

What to do? According to Roux, he picked up his phone and called the coach of FC Martigues, Yves Herbet, whose club had sunk into the relegation zone – and that was relegation to the third division. Herbet remembers things differently: he desperately needed a quality striker, and it was he who called the Auxerre manager. In any case, both men clearly saw a splendid opportunity to address their own ongoing problem, and seized it. But if Éric was easily sold to Martigues, who could do with all the help they were given, how could Martigues be sold to Éric? The ‘Venice of Provence’ – it is criss-crossed by canals and waterways – was the same size as Auxerre; its club was not. But the sun shone on its picturesque city centre. More importantly, Éric and Isabelle could live together, as Aix was less than an hour’s drive away, and Auxerre’s canny manager had made sure to talk to the young woman first, before informing her lover of his suggestion. Martigues would provide the young couple with a small flat, from which Isabelle could commute to work every day. Her response had been enthusiastic, and so was Éric’s. Roux’s plan, cleverly designed, subtly executed, must rank among the most inspired decisions he ever took in over forty years of management. He had judged Cantona perfectly, as a man, and as a player of immense promise. To make sure of the man’s gratitude and of the fulfilment of his promise, he was willing to deprive his team of one of its greatest talents. Let him live on love and play in front of crowds of a few hundred people, if that’s what it takes to calm h

im down; if that’s what it takes to save Éric Cantona.

Another thought had crossed Roux’s mind: ‘Éric’s going to kill himself on the road.’ It’s only as Jean-Marie Lanoé and myself were on our way back to Paris that I remembered a slip of the manager’s tongue which I would have thought nothing of, had my friend not reminded me of Michel N’Gom’s tragic story. You’ll remember that Roux had mentioned Cantona’s battered Renault 5. But Cantona, who had passed his driving test in August, drove a (battered) Peugeot 104. He’d have loved to own one, preferably an ‘apple-green 5TS, with black spoilers’, the car he much later said he dreamt about when he was a child. It was N’Gom who owned a Renault 5. He was a brilliant young player of Senegalese origin who, like Cantona, had been educated at La Mazargue, before joining Marseille, Toulon, Marseille again, and PSG, with whom he won two French Cups. Roux had recruited him for the 1984–85 season. He played ten games for Auxerre, all of them preseason friendlies, before he was killed in a car crash on 12 August 1984, aged twenty-six. N’Gom was a bon vivant who, during his three seasons in Paris, had spent a great deal of his spare time in the nightclubs of the capital. Once at Auxerre, he travelled incessantly in his car to catch up with the friends he had left behind in Paris. It was on his way back from one of these escapades that, surprised by the presence of a tractor in the middle of the road, he crashed a few hundred yards from his home, where his parents were expecting him for Sunday lunch.

Cantona

Cantona